I took computer programming classes at UC Berkeley and spent years trying to get better at programming afterward. While I understood the fundamentals, writing software always felt like it required an enormous amount of time and effort relative to the progress made. The work felt more about managing complexity than solving the underlying problems I cared about.

About a month ago, while exploring some ideas involving AI, I unexpectedly revisited writing code—this time with AI’s help. What surprised me wasn’t that the AI could write code, but that it fundamentally changed where the effort was spent. Instead of wrestling with syntax, frameworks, and coordination details, the work shifted toward defining structure, relationships, and invariants.

A week ago, Ray Ozzie wrote about his own experience collaborating with AI to design and prototype hardware and software systems. Ray is best known for creating Lotus Notes, and for his later work on large-scale distributed systems. His reflections strongly resonated with my own experience—but also highlighted something important.

What took weeks of focused effort in his case unfolded for me in hours.

Not because the problems were simpler, but because the approach was different.

“Having spent much of 2025 transforming the way I write code, a few months ago I decided to see how far I could push myself in collaborating with AI to tackle hardware design.

The project - motivated by conversations with a customer - is nontrivial. Physical and cost constraints; both analog and digital domains; edge compute/storage ML; power challenges. Of course, Notecard for secure cloud backhaul.

I worked on it on-and-off for about 3-4 weeks - surprised not just that the foundation models had so much knowledge of EE, but that they clearly had internalized a vast number of components’ datasheets. Several times I ran into roadblocks where ultrathink or deep research yielded specific choices I’d never have considered.”

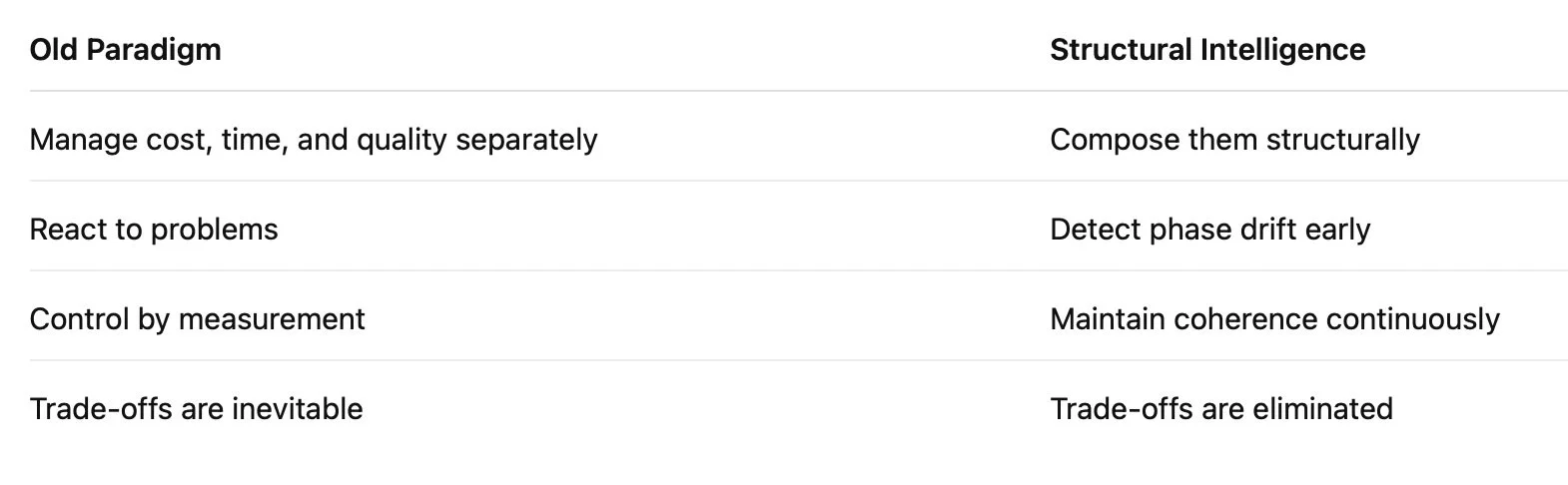

Now I often spend 2–4 hours a day working on computer code. But the work itself is no longer about coding. I’m working on harder, more upstream problems, and the code is simply the executable output of the design.

This ability didn’t appear overnight. It comes from years working in product development as a project and program manager for both hardware and software—guiding execution across teams, understanding how the big picture fits together, and how small decisions compound. Over time, you learn to see systems as composed structures, where relationships matter more than parts, and where symmetries persist even as details change.What used to require explanation and persuasion now shows up as functional proof.

In the past, I might have written a paper or given a conference presentation. Now, in a fraction of the time, I can produce a functional proof—one that can be run, tested, and shared, and that scales to far more people than a paper or presentation ever could.

What also feels right is reaching out directly to Ray Ozzie. After connecting on LinkedIn, I was able to share a few thoughts on how his early technical decisions at Microsoft helped enable the company’s cloud evolution. I’m looking forward to exchanging perspectives on how AI is changing the way we think about coding, structure, and system design.